#Associate Warden Edward Miller

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

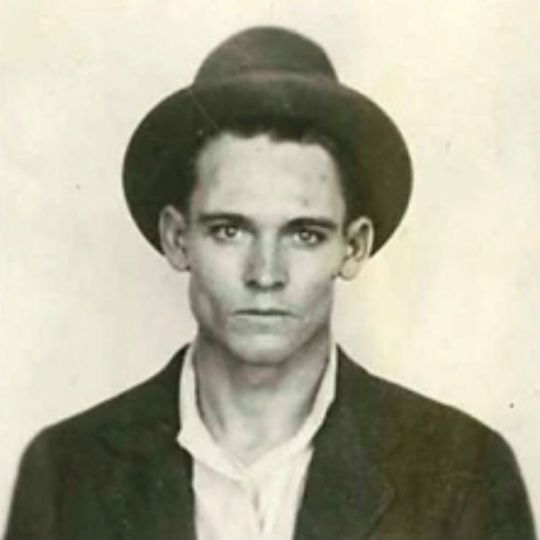

Lawrence James DeVol - One of the Depression's Most Wanted (and most vicious).

Lawrence ‘Larry the Chopper’ DeVol is less well-known than, say ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd or ‘Baby Face’ Nelson, but was no less violent or vicious. Absolutely cold-blooded and criminally-minded, DeVol murdered at least eleven people, probably more. Not content with the murders of at least five citizenss, he murdered at least six law enforcement officers in Iowa, Missouri, Kansas and Oklahoma. Any of…

View On WordPress

#Al Capone#Alcatraz#Alvin Karpis#Arkansas#Associate Warden Edward Miller#Baby Face Nelson#Barker-Karpis Gang#Charles Manson#Chicago#Chicago Outfit#crime#Crime Wave#Depression#Edward Bremer#FBI#Florida#Frank Nash#Frank Nitti#Harry Sawyer#Harvey Bailey#Henri Young#Illinois#Iowa#John Dillinger#Kansas#Kimes-Terrill Gang#Lake Erie#Lake Weir#Leavenworth#Louis Campagna

0 notes

Text

Ten Women Who Changed Criminal Justice in 2018

“Look at me and tell me that it doesn’t matter what happened to me, that you will let people like that go into the highest court of the land and tell everyone what they can do to their bodies.”

The powerful words of 23-year-old Maria Gallagher who, along with her fellow activist Ana Maria Archila, confronted a shaken Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz) on a Senate elevator during the nomination hearings for Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in October, rocked the country this year.

They not only underlined the refusal of women to stay silent any longer about sexual assault in the wake of the #MeToo movement; but they made clear that women’s critical leadership in the multi-front movement to fix our justice system cannot be ignored.

Last year, staff, contributors and readers of The Crime Report chose the collective participants in the #MeToo movement as one of its top “newsmakers” of 2017, and the national debate about sexual misconduct was ranked #2 in our Top Ten stories.

But those choices eclipsed the agenda-setting role played by women at every level of the justice system, in areas ranging from advocacy and research to corrections, courtrooms and policymaking. So this year, we decided to discard our traditional “Top Ten” list in favor of a sharper focus on women as drivers of our national conversation on justice reform.

Our list barely captures the variety and depth of women’s achievements, but we’ve chosen these champions also to reflect the issues that dominated the justice agenda during 2018, from the opioid crisis, gun violence and prison conditions, to domestic trafficking and immigration reform.

They symbolize the emerging roles of women as justice change-makers.

“Women know how to navigate the politics, work across the political spectrum, and get the work done,” said Liz Ryan, director of Youth First, and one of The Crime Report’s 2018 choices.

Ryan is quick to add that women don’t necessarily welcome the spotlight. “My experience is that the women in this movement are about getting the work done and not about the spotlight or the credit.”

We can’t disagree. But it’s also important to note that women bring unique life experiences to the conversation about justice.

“Women have carried for centuries the burden of violence on our bodies,” said Kristin Shrimplin of Ohio’s Women Helping Women program. “We have the scars. We can be trusted that we also have the solutions.

”And frankly, that’s one reason why I strategically partner with men in positions of power. I need them to open the door to the rooms I am not in so that I can bring in the advocacy for, by, and about survivors. We can all be part of effective justice reform this way.”

Here’s our list, arranged in alphabetical order.

Needless to say, readers will have other names they would like to add.

Let us know by email to [email protected] or in your comments on this post, and we’ll be glad to list them next week!

Leann Bertsch

Leann Bertsch

Leann Bertsch, director of the Department of Correction and Rehabilitation in North Dakota and also president of the Association of State Correctional Administrators, has been a leading proponent of ending solitary confinement in prison, as well as improving prison conditions for all inmates. During 2018, she emerged as an influential voice for national prison reform following a trip to Norway and other European countries organized by U.S. prison reform groups. In an interview with NPR, Bertsch said the trip was a defining moment for her, and inspired her to speed up reforms already in the works for North Dakota’s prison system.

“There’s such an overemphasis on punishment and punitiveness,” Bertsch said. “You know Norway talks about punishment that works, and [that means making] society safer by getting people to be law-abiding individuals and desist from future re-offending.”

Armed with the knowledge she brought back from Europe, Bertsch instructed North Dakota prison wardens to drop minor infractions like talking back to a corrections officer, and created a top-10 list of dangerous behaviors, such as serious assault, using a weapon and murder. The transformation of traditional prison culture even extends to nomenklature. This year, the segregated housing units in the state’s correctional facilities were renamed Behavior Intervention Units (BIU).

Carmen Best

Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best

In July, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan named Carmen Best as the city’s new police chief, calling the appointment “an important step in public safety and meaningful and lasting police reform.” In a city that has experienced endemic police morale issues—a court-appointed monitor only this year found the police department to be in compliance with a 2012 federal consent decree prodded by allegations of racial bias, and just a month before Best’s appointment there were reports of a “mass exodus” of rank-and-file officers unhappy about what they said was the city’s lack of support—it seemed like over-optimistic rhetoric. But remarkably, a wide consensus of Seattle opinion, from the police union to prosecutors and community leaders, agreed with the mayor that their new chief represented welcome change.

The 53-year-old Best, the first African-American woman to sit in the Seattle chief’s chair, replaces another female chief, noted reformer Kathleen O’Toole, who stepped down last year for what she described as “personal reasons.” Best, a 26-year-veteran of the Seattle Police Department (SPD), almost didn’t get the job. She was originally passed over as a finalist; but lobbying by community leaders and, surprisingly, the police union, got her back on the list. In an interview this year, Best made clear why she may turn out not only to be a creative force behind the revitalization of the 1,444-officer force, but emerge as a national leader for policing reform.

“Policing has evolved not only nationally but certainly locally,” she said. “Supervisors now spend more time looking at reports, use of force, crisis intervention. We weren’t doing that in the same way [when I started] 26 years ago. Even the fact that we are carrying Naloxone [a drug used to reverse opioid overdose] now, and administering lifesaving efforts in the field—that …wouldn’t have been something that I would have thought we would be doing, but we are doing it because we are engaged in a much more holistic effort in the community.” One notable fact: With Best’s appointment, Seattle’s mayor, police chief and county sheriff are all women.

Christine Blasey Ford

Protesters outside the Kavanaugh hearings, Oct.2018. Photo by Charles Edward Miller via Flickr

The elevator confrontation between the activists and Sen. Flake described above occurred in the midst of Senate Judiciary Committee testimony of Christine Blasey Ford, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Palo Alto University, who accused Supreme Court Judge Brett Kavanaugh (then a nominee), of sexually assaulting her when the two were students in the Washington, DC area. The explosive accusations had raised troubling questions about Kavanaugh’s fitness to serve on the nation’s highest court only days before his confirmation vote.

Ford’s compelling testimony riveted the nation. “I am here today not because I want to be,” she admitted at the start. “I’m terrified.” But although her gripping account of what happened more than three decades earlier didn’t stop Kavanaugh’s confirmation, she effectively empowered many sexual assault survivors to come forward with their own stories and force lawmakers to acknowledge the long-term traumatic effects of male misconduct.

Ford herself has said little publicly about her ordeal since returning to California, except to note that she continues to be a target of threats and harassment, and has been forced to move from her home and leave her job. “I have been called the most vile and hateful names imaginable,” she said. “People have posted my personal information on the internet.” But Ford’s courage in speaking out has forever enshrined her in the pantheon of American female crusaders for justice.

Emma González

A portrait of Emma Gonzalez by “sheringsnippets,” one of 30 artworks of Emma featured in Latina magazine. Photo by Vince Reinhart via Flickr.

Emma González became, for many Americans, the face of the movement for gun control in 2018. She was an 18-year-old senior at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., when a gunman killed 17 people and severely wounded many others in a Valentine’s Day tragedy that added to the tragic toll taken by mass shootings in America. With other students, including Cameron Kasky, Jaclyn Corin and David Hogg, Gonazález launched a gun control movement that quickly spread nationwide. “We are going to be the last mass shooting,” González boldly announced.

The prediction turned out to be premature, but the students’ group, which TIME calls “the most powerful grassroots gun-reform movement in nearly two decades,” persuaded Florida legislators to pass the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act, which raised the minimum age for buying firearms to 21, established waiting periods and background checks for gun purchasers, funds a program for arming selected teachers and hiring more school guards, bans bump stocks, and bans potentially unstable individuals with arrest records from possessing guns. González alone boasts 1.66 million Twitter followers — hundreds of thousands more than the National Rifle Association’s (NRA) 710,000.

González, who graduated in June, is still not old enough to vote; but that hasn’t stopped her from transforming the politics of the gun control movement, even as efforts to change the national argument about guns (and battle the influence of the NRA) have made little headway. “You might not be a big fan of politics, but you can still participate,” she wrote in an Op-Ed for The New York Times in October. “All you need to do is vote for people you believe will work on these issues, and if they don’t work the way they should, then it is your responsibility to call them, organize a town hall and demand that they show up — hold them accountable.”

Kimberly Foxx

Kimberly Foxx

The first African-American woman to lead the Cook County State Attorney’s office in Chicago, Kimberly Foxx has focused on addressing the underlying causes of violent crime, which continues to push Chicago into the top national ranking for murders—even as homicide rates are declining in most cities around the country.

Foxx believes the place to start is community distrust of police, which has affected the ability of law enforcement to identify and arrest shooters, and she made a start in that direction soon after her election in 2016 by sharply reducing or even eliminating arrests and punishment for non-felony offenses—one of the factors that contributes to the alienation of at-risk neighborhoods from the justice system.

In March, she took another bold step by releasing over six years of felony criminal case data on the Cook County Open Data Portal—the first such release of its kind in the country. “For too long, the work of the criminal justice system has been largely a mystery,” she said in announcing the move. “That lack of openness undermines the legitimacy of the criminal justice system. Our work must be grounded in data and evidence, and the public should have access to that information.”

Cristina Jiménez

Cristina Jimenèz,. Courtesy John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

The picture for immigration reform grew darker this year. Stories about children separated from their parents by U.S. immigration authorities and the administration’s continuing anti-immigrant rhetoric dominated the news. But among the bright spots was the organization known as United We Dream, which has spearheaded the cause of some 700,000 young people born to undocumented parents who were allowed to stay and pursue citizenship in the U.S. under the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act. Cristina Jiménez, the co-founder of UWD, was also named by TIME as one of this year’s 100 most influential people, and is one reason for hope that the nation’s core values as a welcoming home for immigrants fleeing persecution and poverty in their native lands will eventually prevail.

Jiménez, who was 13 when she was brought by her parents from Ecuador, emerged from the shadows as a founder of what is now one of the largest immigrant youth-led organizations in the country. Even in the face of setbacks this year in efforts to renew the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, she has helped maintain the political profile of UWD –now a network comprising over 400,000 members and 48 affiliate organizations across 26 states. “My college advisor [in high school] told me that she was not going to help me apply for college, that I couldn’t go to college because I was undocumented,” Jiménez, who at 33 became the youngest MacArthur Fellow last year, said in a published interview. “If I had listened to her, if I had believed her, if I had not pushed back against that and sought out other people to help me, I don’t know what would have become of me.”

The Hon. Catherine Pratt

The Hon. Catherine Pratt

Women’s advocates have long argued that a key tactic in the fight against sex trafficking is to eliminate policies that effectively criminalize the young women and girls trapped by a practice that earns millions of dollars for the traffickers themselves. Judge Catherine Pratt has turned her Superior Court in the Los Angeles suburb of Compton into an example of what can be done.

Pratt, a member of the National Judicial Institute on Domestic Child Sex Trafficking since its launch in 2014, has mandated custody time for many child sex trafficking victims who are arrested on other charges, usually following a public safety analysis. “We try not to use incarceration unless it’s necessary,” she has said. “If I’m concerned about a girl’s safety I’m going to find a therapeutic placement.”

A member of The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, a group that calls on judges to use their “unique position” to prevent sexual exploitation of children by developing a coordinated response by the courts and social service providers to identify victims and use rehabilitative strategies to help them “heal from trauma,” she was a major player this year in efforts by the Center for Court Innovation to re-calibrate attitudes toward prostitutes as victims, rather than criminals. As she put it: “These girls have been victimized by their families, and they have been abused by exploiters who have sold them on the street.”

Liz Ryan

Liz Ryan

Women have long been leaders in the national effort to change how courts and corrections officials treat young people who get in trouble with the law. And in that list, Liz Ryan is often placed in the first rank. A juvenile justice expert who founded the nationally recognized Campaign for Youth Justice (CFYJ), she has focused her efforts most recently on the campaign to close youth prisons and end the punishment-oriented approach that has trapped many young people in a “pipeline” that turns many of them into adult offenders.

Now director of Youth First, a national advocacy organization working to close youth prisons, Ryan has been an influential voice in the national movement to end the practice of trying, sentencing and incarcerating youth in the adult criminal justice system. Some 70 pieces of legislation in at least 36 states have enacted major reforms in areas ranging from raising the age of adult jurisdiction to removing youths from adult prisons over the past decade, and the juvenile commitment rate has dropped by half to its lowest level since the federal government began tracking figures in 1997. But Ryan and her fellow activists believe there’s a lot more work to do.

This year, Ryan released a game-changing report, The Geography of America’s Dysfunctional & Racially Disparate Youth Incarceration Complex, which showed that an estimated 50,000 young people in the U.S. are incarcerated in youth prisons or other out-of-home confinement facilities in the juvenile justice system, a situation that Ryan has described as a national “epidemic” of youth incarceration. “This approach isn’t safe, isn’t fair and doesn’t work,” says Ryan. “It should be abandoned and replaced with less costly and more effective community-based alternatives to incarceration.”

Elaine McMillion Sheldon

Elaine McMillion Sheldon

Filmmaker Elaine McMillion Sheldon’s documentary Heroin(e), released last year, won national recognition in 2018, with an Emmy Award for Outstanding Short Documentary and now an Oscar nomination. Sheldon’s 39-minute Netflix film monitored the struggles of women suffering through the opioid crisis in Huntington, a small town in her native West Virginia. Already a Peabody Award-winner, the 30-year-old Sheldon has been named as one of the “25 New Faces of Independent Film” by Filmmaker Magazine. Her grassroots perspective showcased an often-overlooked truth about the nation’s opioid epidemic. While men comprise the majority of overdose fatalities, there has been an 850 percent increase in synthetic-opioid-related female deaths between 1999 and 2015.

For Sheldon, it’s personal.

“Just looking at my cheerleading squad in middle school and my high school graduating class reminds me how many friends and classmates ultimately became addicted, lost their children or have overdosed,” she said in a published interview earlier this year. But, she added, her documentary can also provide a powerful impetus for young women across the country. “Appalachia is home to a lot of strong women…. I hope young women see them and the leadership they represent, their boldness and their fearlessness, and are inspired.”

Kristin Shrimplin

Kristin Shrimplin

A leader in the fight against domestic violence in Cincinnati, Kristin Shrimplin heads Women Helping Women (WHW), a social justice agency focused on empowering survivors, assisting witnesses of domestic violence and raising awareness about gender-based violence across four Ohio counties.

In 2018, Shrimplin’s agency served more survivors than ever in its 44-year history—and is on target to close the year out at a 20 percent growth rate of over 7,000 survivors.

Just as significantly, WHW it launched a partnership with the Cincinnati Police Department, through a Domestic Violence Emergency Response Team, which allows the agency to immediately tend to victims to provide them with relocation assistance and any other support that they may need in order to get back on their feet.

But Shrimplin is not about to rest on her achievements. “The needle is not moving and has not been moving for convictions for domestic violence, and it is incredibly not moving for sexual violence convictions,” she told The Crime Report.

Recently Shrimplin was instrumental in launching a survivor-centered, corporate certification program, WorkStrong to address policy, training and response for survivors in the workplace. “I’m impatient,” she admitted. “I don’t believe that we need to keep waiting to make things better in this region for survivors.”

Count on hearing more about Shrimplin—and the other women on our list—in 2019.

Megan Hadley is a senior staff writer and associate editor of The Crime Report. Please send us your own nominations for other women who made a difference in justice in 2018.

Ten Women Who Changed Criminal Justice in 2018 syndicated from https://immigrationattorneyto.wordpress.com/

0 notes